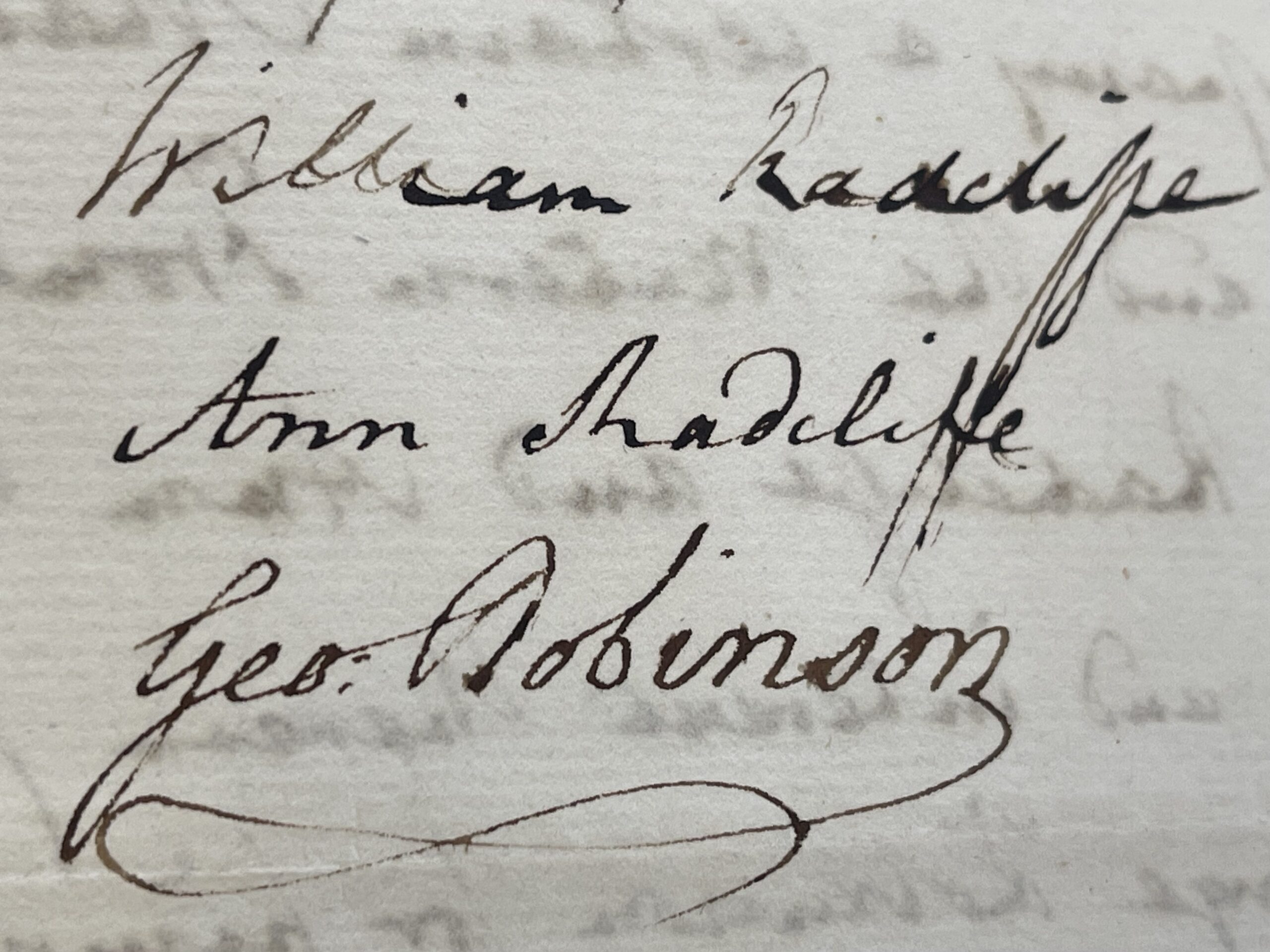

While many of Radcliffe’s contemporaries left behind diaries, letters and journals that provide information about their private lives, manuscript material in Radcliffe’s own hand is scarce. A few letters and a commonplace book are all that appear to have survived after her husband, William, burned her papers after her death in 1823. Understanding more about her life means relying on a handful of facts that have been passed down over the last 200 years.

Ann Ward was born in Holborn, London, in 1764, the same year in which Horace Walpole published The Castle of Otranto, the novel that is often cited as the first Gothic fiction. She was the only child of William Ward (1737-1798) and Ann Oates (1727-1800). In 1787, aged 23, Ann Ward married the journalist and editor William Radcliffe (1763-1830). The couple moved to London, and in 1791 William started working for The Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, a daily periodical with radical, Whiggish sympathies. Meanwhile, Ann was writing prolifically. She had published her first novel, The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne, in 1789, and her second, A Sicilian Romance, in 1790. But it was not until the 1791 publication of her third novel, The Romance of the Forest, that she began receiving significant critical attention. It was also with the publication of the second edition of The Romance of the Forest that Radcliffe first put her name to her work.

In 1794, she published The Mysteries of Udolpho, a four-volume fiction that would go on to become her most well-known novel. This was followed, in late 1796, by The Italian; or, the Confessional of the Black Penitents, a novel containing such well-executed scenes of terror that one reviewer suggested her skill in this kind of writing rivalled that of Shakespeare:

‘She is the greatest sorceress in the terrific that has ever appeared: the murder scene in Macbeth “melts into thin air,” when compared to the black and lowering horrors of the attempted assassination in the Italian.‘

‘Cotemporary [sic] Authors. Estimate of the Literary Character of Mrs. Ann Ratcliffe [sic]’, Monthly Magazine, or, British Register, March 1819.

Between the publication of The Mysteries of Udolpho and The Italian, Radcliffe and her husband travelled around Holland, Germany and the English Lake District, and in 1795 she published her travel writing, A Journey Made in the Summer of 1794, through Holland and the Western Frontier of Germany, with a Return Down the Rhine: to which are added Observations During a Tour to the Lakes of Lancashire, Westmoreland, and Cumberland.

After the publication of The Italian and at the height of her fame, Radcliffe mysteriously retired from public view. She did not publish again in her lifetime, and her final romances, Gaston de Blondeville and St Alban’s Abbey, were published posthumously in 1826 alongside a number of other poems and extracts from her travel journals. Many of her contemporaries speculated over her marked disappearance from the literary scene. Some believed that she had been driven mad by her own terrifying tales; others thought that she had died a premature death. While it is likely that bouts of ill health, including repeated struggles with asthma and chest infections, played a part in her decision to stop publishing, the real reasons for her silence remain unknown.

Radcliffe died on 7 February 1823 after reportedly suffering from a chest infection. Across a number of obituaries, her writing received heartfelt praise and her influence on literature was celebrated. She was lauded as ‘the much-admired author of the “Mysteries of Udolpho,” and other works of imagination and genius, almost equally popular.’1 Her peerless reputation was acknowledged: ‘long known and admired by the world, [Radcliffe was] the able authoress of some of the best romances that have ever appeared in the English language; and which have been translated into every European tongue’.2 Tributes were paid to Radcliffe’s brilliance and her astounding contribution to literature: ‘Her powers of pleasing were singularly great, and the happy combination of various talents which her pieces display, entitled her to the rank of one of the first novel-writers of her age; while the beautiful verses interspersed among her tales, must raise her highly in the estimation of every poetical genius.’3

Throughout the Victorian period and into the early-twentieth century, Radcliffe’s reputation dwindled as the popular taste for Gothic literature began to subside. While there is evidence that she was still read and remembered, she lost the household-name status she once held. Ann Radcliffe, Then and Now, is redressing this imbalance, making Radcliffe accessible to a wide contemporary readership and celebrating her incredible writing and influence.

- ‘The Examiner. London, Feb. 9’, The Examiner, 9 February 1823 ↩︎

- ‘Biographical Particulars of Celebrated Persons Deceased’, The New Annual Register, or, General Repository of History, Politics, Arts, Sciences, and Literature, 1823 ↩︎

- ‘Mrs. Radcliffe’, The Gentlemen’s Magazine: and Historical Chronicle, July 1823 ↩︎